By the time I graduated from Loyola High School in Minnesota, I had read almost everything G.K. Chesterton had written.

Not long after, at St. Louis University, I found myself in the office of Dr. Edward Sarmiento as he shared the story of publishing a poem in G.K.’s Weekly years before I was born. Sarmiento, Professor of Spanish, had received for his youthful efforts a check for one pound sterling signed by G.K. himself.

“You did?!” I sputtered. I expected to see the check itself at any moment pulled from a drawer of his battered office desk.

“I cashed it, Jim.” He said it with that beautifully sad intonation and facial expression the Spanish manage so very well. “I was broke, and needed the money, but that must have disappointed Chesterton. I think he was hoping his autograph would be pay enough.”

Chesterton, among other things, was a canny businessman. Dr. Sarmiento, among other things, was a translator of St. John of the Cross’s poems.

Decades rolled by and my wife and I were at London’s Marylebone Station purchasing flowers and boarding the Chiltern train—destination: Beaconsfield, home of Chesterton. He had made this journey almost daily, traveling to and from his Fleet Street haunts to a town whose name Americans will mispronounce to the amusement of the British. For ever so many readers, his village home might remain a beacon, but it also beckons, and that is how it is pronounced.

Decades rolled by and my wife and I were at London’s Marylebone Station purchasing flowers and boarding the Chiltern train—destination: Beaconsfield, home of Chesterton. He had made this journey almost daily, traveling to and from his Fleet Street haunts to a town whose name Americans will mispronounce to the amusement of the British. For ever so many readers, his village home might remain a beacon, but it also beckons, and that is how it is pronounced.

Flowers in hand, we stood outside his homes, Overroads and Top Meadow. We wondered where the rail line and train station might have been in those days long past. The entrance to Top Meadow was wider than most. It had to be wide or he might have been trapped inside. We lingered before his grave, also that of his wife and secretary. I attempted to translate its Latin inscription all but worn away on a sadly weathered monument.

“You would think with all the people in this world so fond of themselves for revering Chesterton—some of them making money from writing about him—funds could be raised to restore this,” I muttered.

“We are hitchhikers, all of us,” said Kate.

This silenced me. We left our flowers.

An old, old man hailed us from afar as we stood in the cemetery. He claimed to remember Chesterton’s funeral procession from the church to here. “Quite a duck, that man! Cut quite a figure, as you might imagine.” He waved his arms generally in the town centre’s direction. Yes, we could imagine what the farmers and shopkeepers must have thought of Chesterton—cape, swordstick, imposing girth, a London man commuting so far from his work, etc.

This was the first of several ‘pilgrimages’ made while writing Everywhere in Chains and hoping to find some inspiration there, hoping that somehow I would get it right in such close proximity to a man who never ducked tough issues and made friends with staunch opponents. George Bernard Shaw had been among those in his funeral procession.

Another time, Father John Padberg, S. J., my St. Louis University friend of fifty years, accompanied us to the grave and read the inscription. Afterwards, we stopped by the Anglican Church, where Edmund Burke, Beaconsfield’s other famous resident, is remembered. All that remains for evil to triumph is for good men to remain silent. I was far from sure how good I was, but Everywhere in Chains would not be silent.

Another time, Father John Padberg, S. J., my St. Louis University friend of fifty years, accompanied us to the grave and read the inscription. Afterwards, we stopped by the Anglican Church, where Edmund Burke, Beaconsfield’s other famous resident, is remembered. All that remains for evil to triumph is for good men to remain silent. I was far from sure how good I was, but Everywhere in Chains would not be silent.

Mere days after our first Beaconsfield visit, my wife and I met Stratford Caldecott, then at Oxford’s Plater College. He received us cordially, though we arrived on short notice with a letter from Meriol Trevor in hand by way of introduction. (Her Shadows and Images is an Ignatius Press novel). I had been corresponding with the author about her John Henry Newman biography.

We talked of that and the unfortunate loss of Chesterton’s Top Meadow home to real estate developers. Wouldn’t you think…I almost said, another rant coming on. Stratford offered to share his impressive Chesterton collection, swordsticks and a puppet theatre included.

“May I?” I asked.

“Of course.”

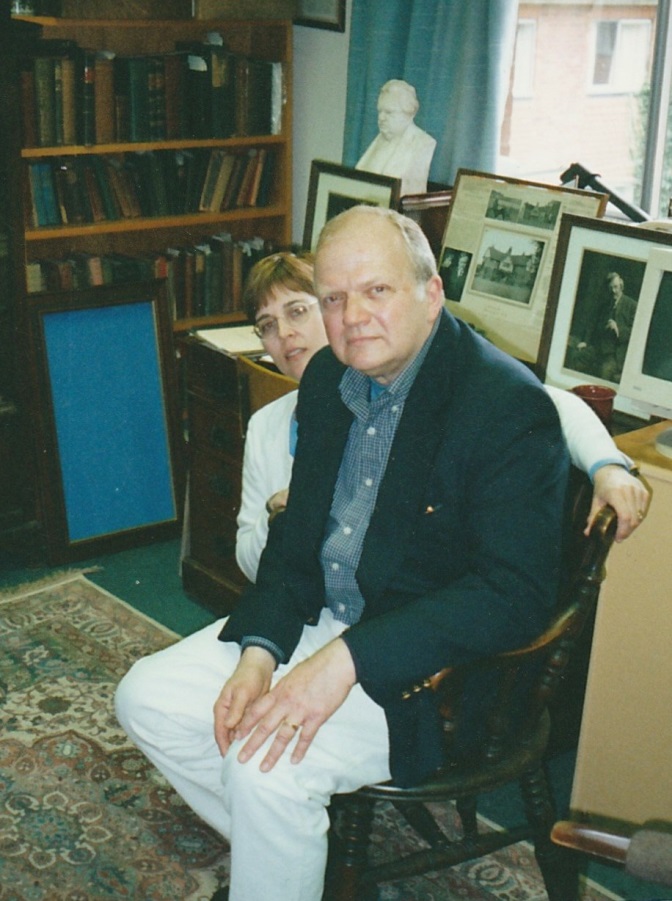

And so I sat in Chesterton’s barrel-backed chair while he snapped a picture. Among other words of praise for the late Stratford Caldecott, let me add redundantly that he was a gentleman to the core. As Chaucer said of the knight in his Canterbury Tales:

He was of sovereign value in all eyes

And though so much distinguished, he was wise

And in his bearing modest as a maid. (Coghill translation)

Kate and I were not exactly following Chesterton, but during our London years, he seemed always to be around a corner, no more so than in Kensington, where two of his homes were two streets from ours, and where the elegant spire of St. Mary Abbot’s, scene of his marriage, dominates an otherwise wretched commercial district.

We would not be writer and writer’s wife if we had not enough imagination to sense his presence even while swimming against the unrelenting tide of relentless shoppers. More than once we imagined Chesterton as a schoolboy making his way home near sunset along this very street. We knew he would always be around the corner somewhere with us as we strolled within the shadow of St. Mary’s. Our thoughts were not in this unimaginably, mindless parade, but with an oh-so-impressionable little schoolboy on his lifelong journey to becoming that engaging ‘duck’ of Beaconsfield.

Back at the very beginning, back at Loyola in 1959 or so, one of the SSND Sisters caught me with my nose in an Image edition of Orthodoxy.

I looked up from a page.

“You know what he once said of neon signs in America? –What an amazing sight, if only you could not read,” said Sister.

I am often tongue-tied at such moments, and so I never did find out whether she referred to those neon signs or to me with my nose where it was. After all, Chesterton and orthodoxy were not especially fashionable in those days on the doorstep of Vatican II.

“We are hitchhikers all,” I should have said, but Kate was off somewhere in my future.

Leave a Reply