Piers Paul Read is perhaps best known for his non-fiction account of the 1972 airline disaster involving Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571, a plane carrying 45 passengers that crashed in the Andes. His book, Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors, became a world-wide bestseller and, in 1993, was made into a film starring Ethan Hawke.

Mr. Read is also an accomplished novelist and playwright, as well as a journalist, biographer, and social commentator. His recent works include the novels Knights of the Cross and Alice in Exile, and the non-fiction titles The Templars: The Dramatic History of the Knights Templar; Alec Guinness: The Authorised Biography; and Hell and Other Destinations.

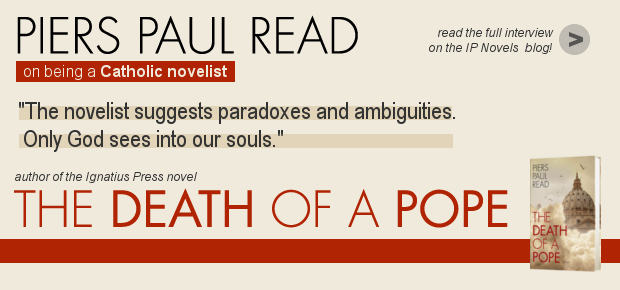

Piers Paul Read’s novel, The Death of a Pope, has garnered acclaim from fellow novelists Ron Hansen and Ralph McInerny. A thriller that intertwines real events with fiction, The Death of a Pope touches on many themes that are hot-button issues in the Catholic Church and the world today.

(Note: this interview was originally published in 2009 in conjunction with the release of The Death of a Pope.)

What inspired you to write The Death of a Pope?

When I was young I was a zealous exponent of Liberation Theology. As I grew older I like to think I grew wiser and came to see how ‘social’ Catholicism, however superficially appealing in the face of the suffering caused by poverty and injustice, in fact falsifies the teaching of the Gospels. This is particularly true when it condones or even advocates the use of violence: as Pope Benedict XVI puts it in his encyclical Spe Salvi, “Jesus was not Spartacus, he was not engaged in a fight for political liberation”. Yet this was precisely the message preached from the pulpits in Catholic parishes and taught in Catholic schools in the last decades of 20th century. The two visions of what charity demands of a Christian confront one another on the issue of the AIDS epidemic in Africa. It is this confrontation that gave me the idea for my novel.

You’ve written quite a bit in both fiction and non-fiction. The Death of a Pope, though fiction, is interwoven with real events, situations, and ideological tensions. Do you see a clear line between what you create and the real world you’re drawing from?

I have always taken the view that a work of non-fiction should be just that, whereas anything is allowed in a novel. In Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors, for example, there are snatches of dialogue which may not use the precise words used by the characters but they are not invented: the exchanges come from my interviews with the survivors.

As a novelist I am a realist and use actual events and institutions to add verisimilitude to the story. There is a danger of tipping the novel into a kind of fictionalised journalism, but that is avoided if the story itself comes from the imagination and the fictional characters have distinct personalities and convincing motives for what they do.

The Death of a Pope begins with a series of quotes, including one from Polly Toynbee from the UK paper The Guardian, claiming that “The Pope kills millions through his reckless spreading of AIDS.” Is this an attitude that is widespread in journalism today?

The pope that Polly Toynbee had in mind was Pope John Paul II but she would level the same charge, after his air-born press conference on the way to Africa in March, 2009, at Pope Benedict XVI. Toynbee is an atheist and militant secularist, and she sees in Catholic misgivings about the use of condoms to prevent the spread of AIDS a stick with which to beat the Church. Her views are widely shared in the secular media, even if they are not so pungently expressed. Liberal Catholics, too, such as the late Hugo Young — a highly influential columnist — sometimes adopted this secularist outlook: he talked of the record of Pope John Paul II as “an offence against elementary tenets of liberal decency”.

In a way, The Death of a Pope is quite critical of the more radical form in which Liberation Theology can manifest itself. Is this based on your own experience with radicalism when reporting from El Salvador?

My misgivings about Liberation Theology and the influence of its exponents in Catholic aid agencies (CAFOD, say, or the Catholic Institute for International Relations) in the 1980s and the support it received in the columns of Catholic periodicals, in particular The Tablet, was confirmed by a journalistic assignment in El Salvador in 1990. The Cross had been replaced in the teaching of the Liberationists priests by the AK-47 assault rifle, and those Catholics who dissented from their point of view risked their lives. “It isn’t easy to speak out,” I was told by a Salesian missionary. “When I tell my bishop in Italy what is happening, he doesn’t believe me. The great untold story is the persecution of the traditional Church.”

Pope Benedict, as Cardinal Ratzinger, warned the college of cardinals shortly after the death of Pope John Paul II that “We are building a dictatorship of relativism that does not recognize anything as definitive and whose ultimate goal consists solely of one’s own ego and desires.” Does this message play a role in the plot of The Death of a Pope?

Interwoven with the political-theological thriller that drives the narrative of my novel there is a triangular love story which reflects some of the moral confusion felt by the young in post-Christian Britain. My heroine, Kate, and the intelligence analyst, Kotovski, are both looking for human love but also a cause in which they will transcend their own ego and desires.

Some of the characters in The Death of a Pope might be described as motivated by a concern for eternal things, while other characters act out of a sincere concern for finite and earthly problems. Do you see this as a conflict that can be resolved?

A tragic aspect of the life of one of the characters in the novel, a Catholic priest, is his inability to convince his niece Kate that true fulfilment can only be found in knowing God through faith in Christ. In some ways he is himself a “failed priest”; and the other characters who are supposedly motivated by a concern for eternal things are seen to be compromised by worldly considerations. The novelist suggests paradoxes and ambiguities. Only God sees into our souls.

In your correct prediction, in The Spectator, of who would be the current pope, you said that “[Ratzinger] is patently holy, highly intelligent and sees clearly what is at stake. Indeed, for those who blame the decline of Catholic practice in the developed world precisely on the propensity of many European bishops to hide their heads in the sand, a pope who confronts it may be just what is required.” How would you evaluate Pope Benedict’s papacy so far?

From the mid-1980s, when I first became aware of the then-Cardinal Ratzinger with the publication of The Ratzinger Report, I have admired him for his patent holiness, his intelligence, his lucidity, his coherence, his charm and the quiet courage with which he insists upon unpopular truths.

How would I evaluate his papacy? His very elevation to the Papacy has routed the “spirit of Vatican II” advocates of an alternative magisterium. His encyclicals Deus Caritas Est and Spe Salvi, the Apostolic Exhortation Sacramentum Caritatis, and his book Jesus of Nazareth, are all superb. His courage and lucidity were clearly apparent in his Regensburg address. I share entirely his insistence that beauty and mystery should return to the celebration of the Eucharist. It was this that gripped my imagination as a child — Benediction as well as the Mass — and I am sure that it is the banality of much of the post-Conciliar liturgy that has made it difficult for a younger generation to perceive the momentous nature of what takes place at Mass.

You’ve known and been friends with many Catholic (and non-Catholic) writers and artists over the years, from Graham Greene to Sir Alec Guinness. Have any contemporaries influenced your own approach to the art of literature?

Graham Green was generous in his appreciation of my novel Monk Dawson, and also of Alive, and I have enjoyed and admired many of his novels. They have not influenced me as much as might be supposed. The urge to write came after reading French and Russian nineteenth-century novels — in particular, Dostoyevsky.

Do you think that today’s artists are still connected with the urge to depict truth and beauty in art? And, as an aside, is it possible to depict beauty and truth without a sense of the eternal?

One of the most potent arguments against the secularist’s belief in blanket progress is to look at the early Italian paintings in one of our national galleries, or to walk into a mediaeval cathedral. Compare the cathedral with an office-block or a shopping mall, or the depictions of the Virgin and Child with contemporary ‘conceptual’ works of art, and it becomes clear that art has indeed suffered from a loss of the sense of the eternal. But it would be unwise to suggest that only sacred art is good art, or that there cannot be genius in the profane. I have been charged by strict Catholics with offending the modesty of the reader in passages in some of my novels, and defend myself with Cardinal Newman’s axiom that “one cannot have a sinless literature of sinful man”. It is also true, as the French Catholic writer Julian Green wrote, that “no novel worthy of the name exists without a complicity between the author and his creatures, and more than complicity — a complete identification. I think that is why,” he adds, “no one has ever heard of a saint writing a novel.”

What is the duty of the Catholic writer, in your opinion?

Writing is a vocation and, as in any other calling, a writer should develop his talents for the greater glory of God. Novels should be neither homilies nor apologetics: the author’s faith, and the grace he has received, will become apparent in his work even if it does not have Catholic characters or a Catholic theme. The question of “the complicity between the author and his characters” can sometimes pose a dilemma: a novelist might show more empathy for, say, Potiphar’s wife, or the elders who spied on Susanna, than the devout might think proper. But it is important for the Catholic writer to demonstrate that he is fully human; that he does not flee from evil but confronts it and disarms it in his imagination with the help of that holy wisdom that comes from faith in Christ.

Leave a Reply