For a year or more when I was a schoolboy, I sent my stories to a nun in a strict religious order. I did not know that she would receive them only after a mother superior examined the contents for signs of wanderlust and wavering.

For a year or more when I was a schoolboy, I sent my stories to a nun in a strict religious order. I did not know that she would receive them only after a mother superior examined the contents for signs of wanderlust and wavering.

The nun had been my classroom teacher for one year before being transferred to a distant school far enough away to seem a distant planet. She had encouraged me to write the cursive letter r so it did not resemble an n.

There is a near infinity of letter r’s and n’s in the universe of words, and from that day forward, every time I wrote anything by hand, her face popped up between the lines. There was no forgetting her, ever, and certainly not for the writer that I would become.

Her face, encased and framed in her habit, was all that I could see. With her pointy nose and merry eyes, she resembled a bird peering from its birdhouse, a laughing bird if you like, and one that loved to tease us boys.

How could I forget what I suppose in my boyish way became a first love?

Next school year, she was gone, leaving her pinched face between school tablet lines I wrote, attempting first stories no one would bother to read.

Since it was no secret where she had vanished, to something sounding like Saint Planet X, I found an address, and began sending my stories her way, week by week and month by month, under a mother superior’s watchful, suspicious eye.

I could never explain to anyone why I kept on writing. And somewhere in the convent of Saint Planet X, I imagined my stories slowly building into a corner, mixing with dust bunnies and protruding from the feet of pastel-colored, holy statues.

I was discreet. I kept my love a secret, though perhaps a hint or two winked from between paragraphs ending in small case r’s and n’s.

I lost count of my stories, and who knows what mayhem transpired in my teacher’s convent when the post arrived on weekend mornings after prayers? Who knows what teasing my first love had to endure?

Nuns are a rambunctious lot. Ask many a bishop or a pope who discovered this the hard way!

Sister-in-the-Birdhouse—as I came to think of her—never responded. I had to imagine her laughter echoing somewhere in the shadowy interior of our rural mailbox where my fingers searched to no avail.

For me, though, another answer lay at the end of the school year when country summer came with its dusty roads and corn rows, blackbirds and murmuring voices in distant fields, too far away to hear for sure and too far away to answer.

Sister-in-the-Birdhouse had taught me to be a writer with imagined readers. She had taught me to persist when there was, and never could be, a response.

I learned to write from the far country of a distant, almost forgotten past and a barely discernible present. She taught me to write for the sheer love of it.

I learned to be a novelist under imagined, watchful eyes, on a street called distant love.

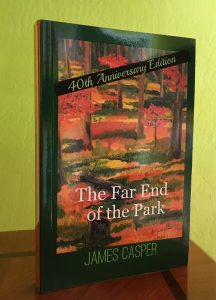

And in the course of time, forty years ago, I wrote a first novel called The Far End of the Park.

Mariana Abeid-McDougall

November 25, 2018 at 6:46 am

You write beautifully.

I have a terrible tendency to rush through sentences, but yours, especially the one about the country summers, made me want to stop and really savour the words I was reading.