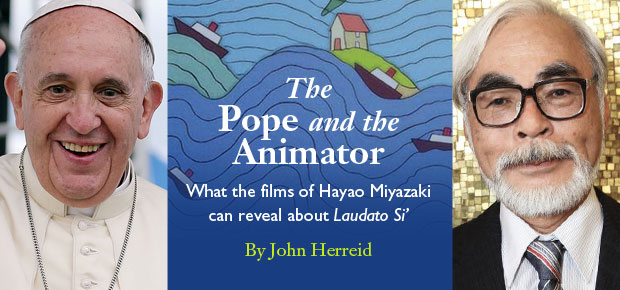

“The aesthetic of the Pope’s reflections (on the tension between man and nature, the tendency of man to use technology to dominate others and the environment, and the ideal of an integral ecology) remind me of the films of Hayao Miyazaki. I think Miyazaki explores similar themes, although from a very different perspective.”

That’s what my wife Aletheia posted online after starting to read Pope Francis’ encyclical Laudato Si’. But how much in common do the views of a Japanese animator and an Argentinian pontiff really have? Let’s take a look.

Who is Hayao Miyazaki?

Japanese animation was regarded in the West for many years as exemplifying cheapness. To cut costs, American animation studios would outsource to Japan. A number of Saturday morning cartoons in the 1970s and 1980s were animated in this way, with fairly uninspiring storylines and pedestrian animation. One of the people who would help change all this was a young animator named Hayao Miyazaki. Cutting his teeth working on different series, he quickly rose to director status. Early work included the first half-dozen episodes of Sherlock Hound, an adaptation of Arthur Conan Doyle’s detective stories recast with animals, featuring glimpses of what would become Miyazaki’s visual hallmark: inventive depictions of fantastic machinery set against a bucolic environment.

When Hayao Miyazaki was a small child his father ran a factory making parts for war planes, including rudders for the famed Mitsubishi Zero. The contrast between the beauty of flight and the destructive power of such weaponry seems to have made a large impact on Miyazaki’s perception of the world. A recurring theme in his animated films is how men and women are easily seduced into thinking they can control nature via technology. In Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, people try to use a genetically modified giant to eradicate a threat. In Princess Mononoke, the industrialist Lady Eboshi attempts to kill a forest spirit who threatens her ironworks. In both cases powers beyond man’s control are unleashed.

When Hayao Miyazaki was a small child his father ran a factory making parts for war planes, including rudders for the famed Mitsubishi Zero. The contrast between the beauty of flight and the destructive power of such weaponry seems to have made a large impact on Miyazaki’s perception of the world. A recurring theme in his animated films is how men and women are easily seduced into thinking they can control nature via technology. In Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, people try to use a genetically modified giant to eradicate a threat. In Princess Mononoke, the industrialist Lady Eboshi attempts to kill a forest spirit who threatens her ironworks. In both cases powers beyond man’s control are unleashed.

Another theme is how selfish choices have an impact beyond the individual, and how finding an adult path in life cannot come through acts of rebellion. In Ponyo (loosely based on The Little Mermaid by Hans Christian Andersen) the daughter of an underwater-dwelling sorcerer and an ocean goddess decides to become human; her impulsive actions cause a tsunami, but in reconciling with her parents balance is restored. In Spirited Away a young girl, Chihiro, goes from rebellious and sullen to responsible and resourceful as she works to free her parents from a curse. Parents aren’t off the hook either: Ponyo’s father must learn that controlling his daughter by force is not the answer. It’s a balance rarely seen in movies aimed at children.

In the documentary The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, which follows Studio Ghibli during the production of Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises and his colleague Isao Takahata’s The Tale of Princess Kaguya, the animator says, “You know, people who design airplanes and machines… No matter how much they believe that what they do is good, the winds of time eventually turn them into tools of industrial civilization. It’s never unscathed. They’re cursed dreams. Animation, too. Today, all of humanity’s dreams are cursed somehow. Beautiful yet cursed dreams.” Lest he seem too dour: on screen he chuckles a bit at his own pessimism.

In 2009 when his film Ponyo was released in the United States, my wife and I had the good fortune to attend “Hayao Miyazaki in Conversation”; an event at the University of California Berkeley. During the conversation he said that he did not believe that humanity can be divorced from nature, so his films show this perspective—natural disasters that are connected to human behavior. “I see hope in the power of nature,” he said, pointing out that along with despair and destruction, disasters bring the hope of renewal—after floods, plant-life springs anew. This echoes something J.R.R. Tolkien said: “Evil labours with vast power and perpetual success—in vain: preparing always only the soil for unexpected good to sprout in.”

In 2009 when his film Ponyo was released in the United States, my wife and I had the good fortune to attend “Hayao Miyazaki in Conversation”; an event at the University of California Berkeley. During the conversation he said that he did not believe that humanity can be divorced from nature, so his films show this perspective—natural disasters that are connected to human behavior. “I see hope in the power of nature,” he said, pointing out that along with despair and destruction, disasters bring the hope of renewal—after floods, plant-life springs anew. This echoes something J.R.R. Tolkien said: “Evil labours with vast power and perpetual success—in vain: preparing always only the soil for unexpected good to sprout in.”

But though he says nature and humanity are connected, Miyazaki also emphasized that the natural world cannot be objectified into matter that we can control at our whim. “Nature is beyond our understanding. So when we made [My Neighbor Totoro], we made sure to make it so you cannot tell where Totoro is looking. We made sure that you can’t tell if Totoro is intelligent or stupid, if he is thinking deep thoughts or none at all.” Man may think he can understand and control nature, but in doing so he courts disaster.

In The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness we learn more about Miyazaki’s personal life. He seems consumed by two things: his animation work and concern for his country. Each day begins with gathering trash in his neighborhood, and every Sunday he goes to the local river to clean up any rubbish. His work on his films is hands-on in the extreme. No script is written. He works directly on storyboards and writes as he goes, sometimes backing up to reverse a previous direction of plot. Miyazaki’s desk is in the same room as the other animators, making him visible and accessible to others at all times. Once a day he stops outside the nursery where the children of his mostly female staff attend school and waves hello. He watches the sunset from the roof, and then returns to his home atelier, where he has assembled large whiteboards tracking the Japanese economy.

He explains his concern for the preservation of livable world for the future: “A child entering this world must sit in another’s chair, eat food from another’s plate, sleep in another’s bed. Only in this way can you find your place.”

He explains his concern for the preservation of livable world for the future: “A child entering this world must sit in another’s chair, eat food from another’s plate, sleep in another’s bed. Only in this way can you find your place.”

When we attended the event with him at UC Berkeley, it was striking that the man interviewing him on stage could only view Miyazaki’s films through an American political lens rather than via a moral framework. Many of his questions were along the lines of “Was this scene a critique of Western consumerism? Is this character emblematic of capitalism? Are your female characters a representation of feminism?” To these questions, Miyazaki seemed amused, and answered with a chuckle that he shows how people behave in moral situations because that’s what people do.

Hayao Miyazaki and Laudato Si’

Though Hayao Miyazaki’s philosophy of life is different in many ways from the Catholic perspective, following his approach to viewing humanity and ecology can help us to a greater appreciation of what Pope Francis says in Laudato Si’. While Miyazaki says man must understand his place in nature, Pope Francis goes further, saying “The best way to restore men and women to their rightful place, putting an end to their claim to absolute dominion over the earth, is to speak once more of the figure of a Father who creates and who alone owns the world.” (LS 75). Where Miyazaki shows the damage humans can do to their environment through hubris, Francis reminds us that the reason we must not so is because “We are not God. The earth was here before us and it has been given to us.” (LS 67). When we see the characters in Miyazaki’s films struggle to find their place in the world, we can turn to Francis again: “Disregard for the duty to cultivate and maintain a proper relationship with my neighbour, for whose care and custody I am responsible, ruins my relationship with my own self, with others, with God and with the earth.” (LS 70). and “Our relationship with the environment can never be isolated from our relationship with others and with God. Otherwise, it would be nothing more than romantic individualism dressed up in ecological garb, locking us into a stifling immanence.” (LS 119).

For Hayao Miyazaki, hope is to be found in how nature heals itself, and how future generations can overcome the faults of their forefathers. But when we saw him at UC Berkeley, he acknowledged that in his darker moments, he despairs of that happening. And indeed, finding hope for the future relies on a hope which goes beyond the material world.

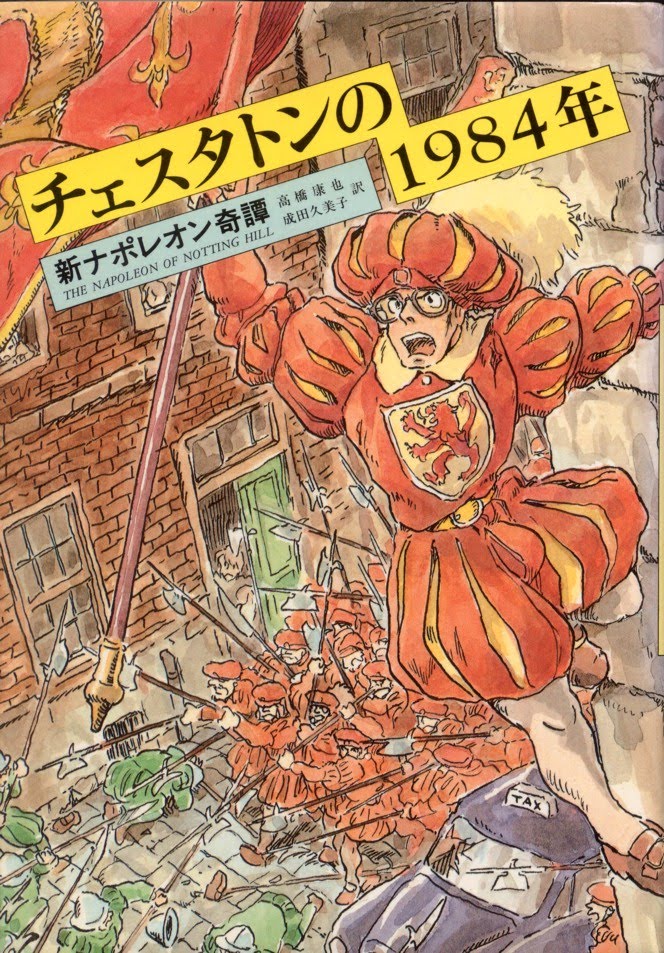

In his films, however pessimism is tempered by a much more hopeful tone. In My Neighbor Totoro, the central family is depicted as close-knit and living in a manner which deeply respects both Japanese tradition as well as the nature they are surrounded by. Even Miyazaki’s more apocalyptic works such as Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Princess Mononoke end on a hopeful note. It’s worth mentioning that the animator is sometime criticized in his own homeland for being too “Western” in his outlook; Miyazaki is fond of fantasy novels from British and American authors, and even once drew a cover illustration for a Japanese edition of G.K. Chesterton’s Napoleon of Notting Hill.

In his films, however pessimism is tempered by a much more hopeful tone. In My Neighbor Totoro, the central family is depicted as close-knit and living in a manner which deeply respects both Japanese tradition as well as the nature they are surrounded by. Even Miyazaki’s more apocalyptic works such as Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Princess Mononoke end on a hopeful note. It’s worth mentioning that the animator is sometime criticized in his own homeland for being too “Western” in his outlook; Miyazaki is fond of fantasy novels from British and American authors, and even once drew a cover illustration for a Japanese edition of G.K. Chesterton’s Napoleon of Notting Hill.

To Miyazaki himself, the words of the Pope should also offer comfort. In the documentary mentioned earlier, the animator frequently doubts the value of his own work. “How do we know movies are even worthwhile?” he says at one point. “If you really think about it, is this not just some grand hobby?” On the contrary, Francis says, “By learning to see and appreciate beauty, we learn to reject self-interested pragmatism.” He goes on to warn, “ If someone has not learned to stop and admire something beautiful, we should not be surprised if he or she treats everything as an object to be used and abused without scruple.” (LS 215).

As a man who has used his immense talents in the world of what Tolkien called “subcreation”, we should give thanks for the beauty that Hayao Miyazaki has passed along to us, and allow that beauty to lead us closer to God and His creation.

Further reading and more

To read Laudato Si’ (Praise Be to You), go to the Vatican website here. You can also purchase a beautiful hardcover edition from Ignatius Press! Click here to see more.

Two of Hayao Miyazaki’s early works can be seen on Hulu: the first six episodes of Sherlock Hound and The Castle of Cagliostro. The first is fine viewing for all ages, the second includes a few cuss words and some innuendo—you may want to preview.

The documentary The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness is currently streaming on Netflix and can also be purchased from various online sources such as Amazon.

The Catholic film critic Steven Greydanus has a fine essay on Hayao Miyazaki on his website, “The Worlds of Hayao Miyazaki”.

Films by Hayao Miyazaki:

The Castle of Cagliostro, 1979

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, 1984

Laputa: Castle in the Sky, 1986 – Review by Steven Greydanus

My Neighbor Totoro, 1988 – Review by Steven Greydanus

Kiki’s Delivery Service, 1989 – Review by Steven Greydanus

Porco Rosso, 1992 – Review by Steven Greydanus

Princess Mononoke, 1997

Spirited Away, 2001 – Review by Steven Greydanus

Howl’s Moving Castle, 2004

Ponyo, 2008 – Review by Steven Greydanus

The Wind Rises, 2013

Images at top: “Hayao Miyazaki” by Thomas Schulzdetengase @ Flickr. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

“Pope Francis Korea Haemi Castle 19 (cropped)” by Korea.net / Korean Culture and Information Service (Photographer name). Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Tere

July 23, 2015 at 12:20 pm

Thanks! Very illuminating!

Rosalie

July 23, 2015 at 7:52 pm

I remember seeing Princess Mononoke for the first time when I was beginning my college years. It was my first Miyazaki film, I was struck by how deep and painstakingly beautiful the animation and story is, and from then on, I have been hooked on anything Studio Ghibli. Not even Disney can make a movie such heart. Whether it’s My Neighbor Totoro or Spirited Away, they will make you laugh and cry. Mr. Miyazaki truly has a gift, and I was so sad when he announced his permanent retirement this year.

John Herreid

July 23, 2015 at 10:49 pm

The first of his movies I saw was My Neighbor Totoro. It was a favorite of my youngest sister for several years, so I made her a couple of carved wooden Totoros to play with.

My children’s favorite tends to waver between Totoro and Ponyo, but as they grow older I’m sure Miyazaki’s other films will become just as beloved.

Timothy Jones

July 23, 2015 at 10:50 pm

Thank you for this thoughtful article! I hope to use this, along with perhaps the documentary you mentioned, to stir some discussion with my art students.

John Herreid

July 23, 2015 at 10:52 pm

Thanks, Tim! I’m delighted it can be of help!

Ignatius Press Novels | Friday Links

July 24, 2015 at 6:34 pm

[…] don’t miss this week’s posts here at the Ignatius Press Novels, my own piece on Hayao Miyazaki and Pope Francis, T.M. Doran on Harper Lee, and a link to a new interview with Piers Paul […]

Christopher Hagen

July 28, 2015 at 3:50 am

When I read Laudato Si the artist whose work seemed akin to the Catholic vision of creation was the Minnesota folk songwriter, Peter Mayer. Although now a lapsed Catholic, his Jesuit formation and Catholic sacramental view of creation imbue his finely crafted songs with a rapturous and humble regard for creation. I didn’t think of Miyazaki films when I read Laudato Si, but as soon as I saw the headline of this article, I knew his films would make thoughtful viewing alongside the encyclical. Thank you for bringing Miyazaki to the discussion table of Laudato Si.

John Herreid

July 28, 2015 at 10:30 am

Thanks, Christopher! I will have to check out Mayer’s work.

I have to say that the first writer who came to mind when I read through Laudato Si’ the first time was Wendell Berry and his idea of the Great Economy. There was a good piece by John Murdock in First Things titled “The Pope and the Ploughman” discussing Berry and Pope Francis.

Fr. Augustine, OP

February 25, 2016 at 11:14 pm

Thanks so much. The combination of these two brings out a third kind of beauty which is appreciated.