“A complete poem is one where an emotion has found its thought and the thought has found its words.” — Robert Frost

In his otherwise disparaging review of Dr. Ian Ker’s G. K. Chesterton: A Biography, the late atheist critic Christopher Hitchens noted that he and Ker were in agreement “on the high quality of Chesterton’s poems.” Hitchens had many unkind comments about a whole host of Catholic writers but on the subject of Chesterton’s poetic works, he found within the rhymes “his magic faculty of being unforgettable.”

This will come as a surprise for many, even as G. K. Chesterton’s work has undergone something of a renaissance with practically all his work being brought back into print. However, few are aware of his poetry outside of his drinking poems and what W. H. Auden called “the best pure nonsense verse in English.” Chesterton’s poetry sold well in his own time and earned him praise, but even the great Bombastic Journalist thought of himself as “a very minor poet.” So it is that few people today neither read much of his poetry nor are familiar enough with it to see the brilliance hiding beneath the careful rhymes and whimsical verse.

With the renewed interest in Chesterton and his work, we should not neglect the contribution he made to English verse, which is at times child-like as it explores the deep mysteries of faith and existence with the very heart of a child he was so praised for possessing. While his poetry might have seemed archaic compared to the great modernist poets of the twentieth century, his desire to express beauty and truth within a traditional rhyming and sometimes iambic form left a legacy of good and unforgettable poems that are worthy of study and memorization.

Wine, Water, and Song

The majority of those who have encountered Chesterton’s poetry have most likely heard his drinking ballads as they are recited before or after a pub crawl. With the right cadence, these particular verses are a golden mean between traditional drinking songs and rowdy poetry. His most famous one is “The Rolling English Road,” a poem against temperance societies and possible prohibition in England:

Before the Roman came to Rye or out to Severn strode,

The rolling English drunkard made the rolling English road.

A reeling road, a rolling road, that rambles round the shire,

And after him the parson ran, the sexton and the squire;

A merry road, a mazy road, and such as we did tread

The night we went to Birmingham by way of Beachy Head.

The rolling drunkard and road in this case is part of a theme underlying much of Chesterton’s work: looking back on the English way of doing things in defense against what he saw as the rising tide of the cult of progressivism. Like many historians, Chesterton saw the pub and the pint as essential to the English soul as the ancient footpaths of central England. Even in something as simple as a pint of ale, the Chestertonian sees a highly traditional practice worth protecting and preserving.

This particular view of the pub as a citadel against modern errors was also echoed in “The Ballad of an Anti-Puritan”:

The new world’s wisest did surround

Me; and it pains me to record

I did not think their views profound,

Or their conclusions well assured;

The simple life I can’t afford,

Besides, I do not like the grub —

I want a mash and sausage, `scored’—

Will someone take me to a pub?

The jovial tone of Chesterton obfuscates his desire for a more earthly life of drink and song, which he praises greatly throughout his poetic oeuvre, over and against the discussions and plans of society’s elite. In much of his work Chesterton lampooned the modernist poets as well as those with strange, new philosophies in such verse that remains memorable even when the subjects become forgettable.

Against the rise of new philosophies and cultural approaches to the old pagan beliefs, Chesterton found a way to question their underlying ideas while defending what he saw as the virtue of the old pagans and the wisdom of his Christian faith:

If I had been a Heathen,

I’d have piled my pyre on high,

And in a great red whirlwind

Gone roaring to the sky;

But Higgins is a Heathen,

And a richer man than I:

And they put him in an oven,

Just as if he were a pie.

Now who that runs can read it,

The riddle that I write,

Of why this poor old sinner,

Should sin without delight—

But I, I cannot read it

(Although I run and run),

Of them that do not have the faith,

And will not have the fun.

Songs of War and Grief

While Chesterton was known for his jolly demeanor—he was described by Dorothy L. Sayers as the “beneficent bomb”—he was certainly not one to mistaken his desire for innocence with naivety. His poetry during the Great War tended to be a call to remember why England was great, even in the midst of a brutal war, but to also reflect on the loss of England’s sons—including his brother, Cecil.

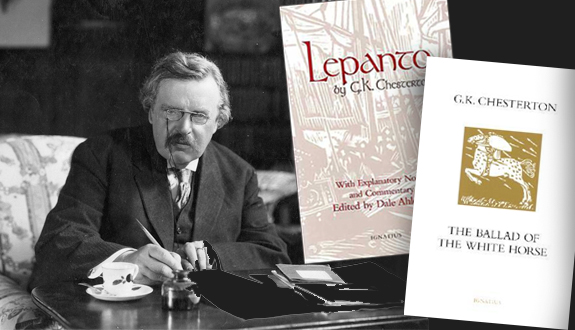

Lepanto was his great poem written in 1911 and first published during the War; it would serve as an inspiration to the men in the trenches who saw some parallels with Don John of Austria’s great sea battle and the struggle of the Allies on land, sea, and air. The ballade of Chesterton’s Lepanto is a rollicking and rousing tale of martial exploits and bravery that sets the pace of a grand adventure.

Torchlight crimson on the copper kettle-drums,

Then the tuckets, then the trumpets, then the cannon, and he comes.

Don John laughing in the brave beard curled,

Spurning of his stirrups like the thrones of all the world.

Holding his head up for a flag of all the free.

Love-light of Spain – hurrah!

Death-light of Africa!

Don John of Austria

Is riding to the sea.

Shortly before the publication of Lepanto, Chesterton wrote one of the last great English epics about King Alfred the Great and his struggle against the Danes. The Ballad of the White Horse is a poem on the grandest scale, covering the defeat of Alfred before he bands together the chieftains to fight the great victory over the Danes at the Battle of Ethandun.

The brilliance and impact of this poem, originally published in 1911, cannot be overstated. It had a profound impact on a young J. R. R. Tolkien (though he would reconsider it later in life) as well as Conan the Barbarian author Robert E. Howard. Famed novelist Graham Greene, who had called Chesterton an “underestimated poet,” compared The Ballad with T. S. Eliot’s landmark The Waste Land, stating: “Put The Ballad of the White Horse against The Waste Land. If I had to lose one of them, I’m not sure that…well, anyhow, let’s just say I re-read The Ballad more often.”

The Ballad was carried by many soldiers in the First World War and Chesterton received letters of gratitude from widows and wives for writing it. Likewise, during the Second World War, when the The Times wrote of the Allies’ defeat at the Battle of Crete the article ended with the words of the Virgin Mary to King Alfred:

I tell you naught for your comfort,

Yea, naught for your desire,

Save that the sky grows darker yet

And the sea rises higher.

Night shall be thrice night over you,

And heaven an iron cope.

Do you have joy without a cause,

Yea, faith without a hope?

We can imagine that the great journalist and poet of Beaconsfield was filled with joy to see his work having a positive impact on his fellow Englishmen.

As much as he may have loved his nation, Chesterton was not always the jingoist flag-waver who cheered the war effort. Writing in The Defendant (1901), Chesterton stressed a love of native land against the “lust of territory” and the desire to conquer and hold lands. He remarked on the new patriotism sweeping Europe,

‘My country, right or wrong,’ is a thing that no patriot would think of saying except in a desperate case. It is like saying, ‘My mother, drunk or sober.’ No doubt if a decent man’s mother took to drink he would share her troubles to the last; but to talk as if he would be in a state of gay indifference as to whether his mother took to drink or not is certainly not the language of men who know the great mystery.

The horrors of losing friends and family to war would also move him to write one of the darkest and most damning anti-war poems ever printed in the English language, Elegy in a Country Churchyard:

The men that worked for England

They have their graves at home:

And bees and birds of England

About the cross can roam.

But they that fought for England,

Following a falling star,

Alas, alas for England

They have their graves afar.

And they that rule in England,

In stately conclave met,

Alas, alas for England,

They have no graves as yet.

Chesterton’s brother had died while serving England, shortly before the Armistice, and that great loss induced one his more melancholic moods.

While Chesterton was seen as a generally happy man, some scholarship indicates that he may have battled a depressive mood now and again. Certainly he wrote about the afflictions of his mind while a young man, and the death of his beloved brother caused him to compose some uncharacteristic harsh words in letters as well as meditations on suffering. In one of these spells he wrote A Prayer in Darkness which, to this author’s mind, is Chesterton’s most moving poem:

THIS much, O heaven—if I should brood or rave,

Pity me not; but let the world be fed,

Yea, in my madness if I strike me dead,

Heed you the grass that grows upon my grave.

If I dare snarl between this sun and sod,

Whimper and clamour, give me grace to own,

In sun and rain and fruit in season shown,

The shining silence of the scorn of God.

Thank God the stars are set beyond my power,

If I must travail in a night of wrath,

Thank God my tears will never vex a moth,

Nor any curse of mine cut down a flower.

Men say the sun was darkened: yet I had

Thought it beat brightly, even on—Calvary:

And He that hung upon the Torturing Tree

Heard all the crickets singing, and was glad.

A Prayer in Darkness deals with some darker themes, much like his more famous A Ballade of Suicide, but it is also a poem of hope and gladness. The speaker of both poems is not able to change everything, but can find the things in life and in God that enable him to say, “I think I will not hang myself to-day.” It is not a mere empty comfort or a song of self-help but is in fact an acknowledgement of the state of the world and the troubles of the mind while still possessing the faith, hope, and tenacity to seek out what makes life worth living.

Chesterton’s poems range from the rollicking drinking verses to the exciting fantasies and back to the poems seeking hope when life can seem so bleak—and even one that acknowledges the horrors of jingoism and warfare. As with his prose, Chesterton wrote so many pages of verse that many of them had to be hunted down by his wife and publisher before they could be collected. As publishers such as Ignatius Press bring his poetry to more readers, we ought to raise our glasses and bow our heads in gratitude that the Creator had given us a bard who could speak to the fullness of human experience in rhyme and meter.

This article first appeared in Catholic World Report and is reprinted with permission.

S.C. Enver

April 9, 2015 at 2:14 pm

We need a single volume collection of Chesterton’s poems from Ignatius!

Tom

April 13, 2015 at 10:52 am

A most welcome article, Mr. Lichens. Thank you.