Lying there, for the few moments before Maes and the infirmarian raised him, he believed. Perhaps it was exhaustion that lowered the barriers pride and custom had long raised in him; perhaps the lucidity and intuitive accuracy of the vision he had beheld. He might never know, fully. But lying there, he wept—for those he had beheld, for his own past unbelief, for Elva… but mostly and in what amazement he was capable of, for the icy vanity of his own people.

—From Dayspring by Harry Sylvester. This passage follows a scene where the protagonist, Spencer Bain, takes part in a penitential procession, his identity hidden from others under a robe and hood.

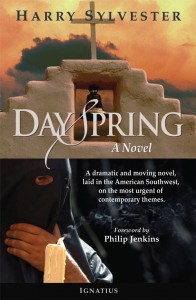

In the novel Dayspring by Harry Sylvester, first published in 1945, we follow Spencer Bain, an anthropologist investigating the religious practices of Los Penitentes, a penitential Catholic brotherhood in New Mexico that engages in severe penitential acts. In order to gain entrance to the brotherhood, Bain affects a religious conversion. But then he begins, to his disconcertment, to actually feel sorrow, to feel penitent for his many sins. Married with no time for children, he and his wife obtained an abortion. He hasn’t been faithful. He has lied and used others for personal gain. The ironic, sophisticated distance he had been able to place between himself and the reality of sin is stripped away as he shoulders the practices of the Penitentes; praying, fasting, carrying a heavy wooden cross, whipping himself.

In the novel Dayspring by Harry Sylvester, first published in 1945, we follow Spencer Bain, an anthropologist investigating the religious practices of Los Penitentes, a penitential Catholic brotherhood in New Mexico that engages in severe penitential acts. In order to gain entrance to the brotherhood, Bain affects a religious conversion. But then he begins, to his disconcertment, to actually feel sorrow, to feel penitent for his many sins. Married with no time for children, he and his wife obtained an abortion. He hasn’t been faithful. He has lied and used others for personal gain. The ironic, sophisticated distance he had been able to place between himself and the reality of sin is stripped away as he shoulders the practices of the Penitentes; praying, fasting, carrying a heavy wooden cross, whipping himself.

The cultural elites gathered in the area are artists, writers, and other academics. Their interest in local customs is that of a superficial museum patron. They are there to observe and exclaim over the colorful processions and gawk at what they regard as eccentricities of fanatics. They can’t imagine the Penitentes are sincere—the brotherhood must be made up of sadomasochists obtaining sexual thrills from their acts. As for Spencer Bain himself, the sincere religious feeling he has begun to experience terrifies him, and he makes an effort to hide his awakening faith from others in his social circle.

….

Here I have to confess: I see myself in the cynical elites. The open, raw expression of faith that can be found in many cultures makes me uncomfortable. Because that isn’t how I express faith it is often hard for me to understand it, so it’s easy for me to fall into the trap of assuming insincerity (“They must be putting on an act!”) if someone is doing things such as going around giving out hugs or engaging in passionate, spontaneous prayer. I’m a buttoned-down Catholic, and that’s unlikely to change. (I might also add here that I’ve met some Catholics attracted to the Charismatic movement who had a hard time believing that buttoned-down types were sincere in their faith: if not, why weren’t they showing it with loud shouts of joy?)

What can be dangerous for people like me is allowing discomfort with emotional intensity to curdle into that same cynical distance the elites are depicted as having in Dayspring. I’ve seen a number of fellow Catholics express astonishment that anyone could think Pope Francis is sincere in his raw, emotional, and open way of spontaneously engaging in gestures such as embracing the sick and disfigured, or his penchant for exaggerated metaphor and an off-the-cuff speaking style. I mean, he has to be putting on an act for the cameras, right? That can’t be sincere. Bring back a more formal papacy. Enough with the emotion.

Cynicism of this kind is like pouring acid onto faith and relationships. Corrosion begins to seep into how we see others. It destroys our ability to see the good in people and makes us always assume underlying motives for words and actions rather than accepting anything at face value. Trust is denigrated as naiveté. Attempts to display the attractiveness of faith are regarded as mere happy-talk by false optimists. We rationalize it by saying we are merely being realists, looking at things through adult eyes. It’s poison, self-administered bit by bit. And it’s an attractive poison for people like me.

….

The end of Dayspring is challenging. Spencer Bain finds that he is unwilling to share his stirrings of faith with his social circle lest he be judged a fool or a hypocrite. He feels a fraud both among them and among the Catholics. The duplicity begins to disgust him, and thus he must make a choice: fully embrace the sincerity of openness to others and openness to faith, or return to the insulation of ironic and cynical distance. And so must we make a choice. While most of us Catholics aren’t necessarily wrestling between faith and atheism, many of us are torn between a comfortable cynicism that allows us to judge others at all times or the uncertainty of trusting the faith of others.

What choice do we make?

Leave a Reply