Novels often fall into the trap of offering easy redemption. The wayward soul sees the error of his ways, has a quasi-mystical experience, and sets off on the road to the straight and narrow. It’s what we want to happen—even if it sacrifices some of the reality of human behavior in doing so.

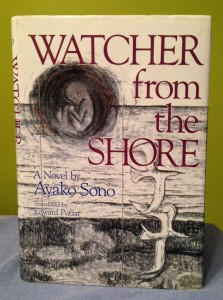

Watcher from the Shore doesn’t offer any of this sort of catharsis. Written by the Japanese Catholic novelist Ayako Sono, it is about as unsentimental a novel as you could imagine. Her novel offers a glimpse into a culture that can appear to be rigid and emotionally repressed to Western eyes. At the same time, the book allows the reader to view Christian morality from the outside, stepping into the shoes of an agnostic gynecologist who sees his participation in abortion as balanced somewhere between moral neutrality and a positive good for society.

Watcher from the Shore doesn’t offer any of this sort of catharsis. Written by the Japanese Catholic novelist Ayako Sono, it is about as unsentimental a novel as you could imagine. Her novel offers a glimpse into a culture that can appear to be rigid and emotionally repressed to Western eyes. At the same time, the book allows the reader to view Christian morality from the outside, stepping into the shoes of an agnostic gynecologist who sees his participation in abortion as balanced somewhere between moral neutrality and a positive good for society.

Sadaharu Nobeji operates his clinic near the shores of the Pacific Ocean. In the not-so-distant past, it was common for people in this part of rural Japan to discard newborn infants if they had birth defects or were otherwise unwanted. Sadaharu tells himself that it’s a good thing that he is now there to offer the more humane alternative of abortion, yet despite his insistence upon a clear conscience he keeps bringing the topic up in conversation with his best friend, a widowed Catholic woman named Yoko Kakei. During a dinner visit, Yoko introduces him to a Catholic priest, Father Munechika.

In his first conversation with Father Munechika, Sadaharu gives one of many of his defenses of performing abortions:

“Let’s suppose I become a Christian. I borrow a cross from the church, without paying, Father, and set it up on the roof of my clinic in place of the lightning rod. My patients arrive, and when they see the cross I will say: ‘Look there! I’m so afraid of God I certainly will not perform abortions.’ Now, Father, I ask you; What will that solve? …I’ll tell you what would happen. They would skip the sermon and go to another clinic for their abortions. That’s all. And though I say it myself, if you will pardon me, I’m clever with my hands and my operations are good. Frankly, it’s better for the patients that I do their operations instead of some other doctor.”

The clinical distance Sadaharu cultivates between himself and objective morality is mirrored in his distance from his wife. He allows his lonely wife to indulge in expensive vacations abroad and luxury items, and he looks the other way when she engages in affairs with other men. It’s not his business what she does, he tells himself, and besides—isn’t it kinder to let her have these things? It’s only rarely that he acknowledges that perhaps her unhappiness is driven by his own behavior. He does have a warm relationship with his daughter, but as in his relationship with Yoko, he retreats into ironic humor whenever more serious topics arise.

There’s also the fact that many of the women he sees for abortions are obviously being pressured into terminating their unborn child by family members, lovers, or societal norms. In one case, a mother-in-law has realized that her son’s wife was pregnant before they married. She demands that the child be disposed of—their powerful and wealthy family can’t be the subject of gossip. Sadaharu attempts to get the young bride to voice her own feelings on the matter, but she doesn’t find the courage to speak her mind until it is too late.

The doctor isn’t the only one wrestling with questions about morality. His friend Yoko is also deeply troubled when she finds herself unable to eschew formal politeness and voice her objections to a friend’s decision to abort a child likely to be born with Down’s syndrome. “What good is my religion, I wonder,” she says. Sadaharu tries to reassure her that she’s merely being open-minded, but this is not a reassurance she wants to hear.

How does one believe in goodness in the face of suffering? Of medical abnormalities? Of death? Ayako Sono is unsparing in the details of the cases Sadaharu comes across: a Down’s syndrome infant blinded by his parent’s beatings, a child born without eyes, a young patient who discovers she is intersexed, a baby killed at birth to cover up an act of incest. He isn’t a man from a Christian background, and his curiosity about faith seems born of a puzzlement that anyone could think that goodness or God could be at work in the world. Holding the world at arm’s length seems like the only sane response. But that curiosity keeps growing as he seeks out how Father Munechika reacts to the problem of suffering, why Yoko keeps her faith. Other unlikely sources that lead him further into the idea of faith as consolation include the Epic of Gilgamesh and the music of Elvis Presley.

At one point in the novel, Sadaharu has been oddly shaken when an abortion operation fails. The woman comes back to the clinic for a refund, explaining that she is still pregnant and that she has decided to keep the baby. The doctor decides to visit Father Munechika and discuss the matter with him. The priest tells him that the failed operation is his responsibility. “You have caused a life to exist.”

The conversation continues:

“That’s a very depressing way to produce life, Father. Just what am I in that case? In your way of speaking, I’m an instrument of God. But I’m a rather dirty instrument, I’m afraid.”

“Dirty? That’s not so clear, I think. Neither the good nor evil of humanity, nor the process of becoming so, is at all simple until we know the results.”

Before the doctor leaves, he asks to see the parish church. As Sadaharu looks at the church’s painting of Jesus as a carpenter, he notes that the hands of Christ in the image are dirty.

Father Munechika replies:

“But even the hand of God is dirty when He is at work. If His hands are not dirty, then He is not actually working.”

Sadaharu pretended not to have caught the priest’s words.

Watcher from the Shore doesn’t end with a conversion, an emotional speech, or overt repentance. It ends with the same questions that it began with. It’s up to us to work out where the answers lie.

Leave a Reply