Readers of fiction involving ordinary people, everyday life, and easily imagined predicaments, often suspect such stories must be autobiographical. Sometimes this is a correct assumption, as in the case of Charles Dickens’ classic David Copperfield, and often it is not, as in the case of another classic, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. Both novels seem true-to-life and believable, though we cannot be certain that Defoe even knew how to swim, so adroitly did he blur lines between fact and fiction.

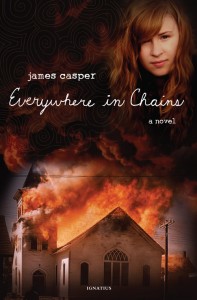

Everywhere in Chains, my recently published Ignatius Press novel about a family with a mentally ill loved one in prison, has already invited speculation that I must have had firsthand experience with prison life. No one has gone so far as to ask me – yet – if by chance I am an ex-convict or if I have a close family member behind bars, an arsonist perhaps. Given the harrowing prison conditions described in Everywhere in Chains, I do not blame them for wondering, and yet if we insist that writers limit themselves to firsthand experiences, most of us would be restricted to writing about breakfast, etc. Sometimes careful research, logic, other people’s experiences, and a bit of imagination will suffice.

It often happens, though, that a metaphorical fire recalled from long ago, years later will ignite a creative spark. For my novel, the fire from long ago was an interlude when my father, a shattered World War II veteran, spent a few months in a county jail on the very street of a nearby Catholic school where I was in the second grade struggling with cursive writing and a rather out-of-sorts novice teaching Sister.

I have vivid memory of walking past the jail twice each day with my much more pleasant sibling sister, then in the first grade. We would often stop while going and coming, and briefly stare across the street at the gray stone building whose windows were too obviously barred. It was as close as we could come. I am sure this was one of those moments calling to mind Felix’s spider in my novel, too frightening to view for long and yet holding us in its grip with its strange, compelling attraction. Dad was in there somewhere. Months went by before we actually saw him again.

I have vivid memory of walking past the jail twice each day with my much more pleasant sibling sister, then in the first grade. We would often stop while going and coming, and briefly stare across the street at the gray stone building whose windows were too obviously barred. It was as close as we could come. I am sure this was one of those moments calling to mind Felix’s spider in my novel, too frightening to view for long and yet holding us in its grip with its strange, compelling attraction. Dad was in there somewhere. Months went by before we actually saw him again.

You never forget moments like that. No matter how old you are, they never go away, and this particular memory years later led me to Everywhere in Chains. The circumstances of my protagonist Penelope and her family are very different from those of my family at that time, and so in that sense the story is not the least autobiographical, but my childhood experience is certainly there somewhere.

As Penelope’s Aunt Charlotte says, speaking to Father Ulrich of her brother, “When someone you love is in prison, your heart goes there with them and stays there as long as he is there.” This sentiment was the spark from a long ago fire. From that point onward I could feel at home with my touchstone emotion, because day by long-ago day our hearts had also been behind bars with our dad. Brief as it was and young as we were, that feeling from a distant past melded with the novel just begun. Penelope’s heart never drifted far from her father’s despite attempts to keep the truth from her. It was easy to imagine what followed: in that sense we all had spent time in jail. We were all victims of punishment.

I should add that my father was suffering from what today is called post-traumatic-stress syndrome. He had survived some of the bloodiest action in the latter stages of World War II. In those days, people did not thoroughly grasp how those experiences could affect not only the veteran, but his family when the war came home with him.

Dad was an amazingly courageous man, a much decorated soldier with two Purple Hearts. The offense that confined him to a county jail for a few months, non-violent and minor as it was, these days might have sent him to prison. A man adrift in memories that would never leave him, he simply and understandably lost his way in a world that seemed unprepared to know what he had been through. Veterans, in fact, would gather around tables in servicemen’s clubs to exchange stories they could share with no one else. With the war over, those on the so-called home front were eager to put it all behind them. It was far less easy for those who had seen action. That the war had come home is an idea we have only caught up with these days in the midst of more recent conflicts.

Nevertheless, in some ways – as my priest character Father Ulrich points out – the world of the early fifties, was a kinder, gentler world than this one. For example, judges had more freedom to consider all the circumstances, not simply the cold facts of a law that had been broken by a broken man. In my view, that was more the way a merciful Christ looked at things when he challenged the men intent on stoning the adulterous woman.

Nevertheless, in some ways – as my priest character Father Ulrich points out – the world of the early fifties, was a kinder, gentler world than this one. For example, judges had more freedom to consider all the circumstances, not simply the cold facts of a law that had been broken by a broken man. In my view, that was more the way a merciful Christ looked at things when he challenged the men intent on stoning the adulterous woman.

Thanks to a judge who had the freedom to be Christ-like, my family’s story had a happy ending. Dad was returned to a family he loved and who loved him. He was never again behind bars. Though memories of the war gradually receded but never went away, at least he was home again for breakfast.

I suppose I should say, for the benefit of those who have read Everywhere in Chains – as a famous radio broadcaster used to say – “Now you know the rest of the story.”

Leave a Reply