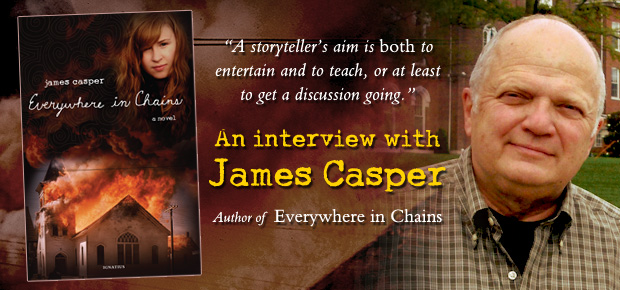

Everywhere in Chains is the first novel by James Casper published by Ignatius Press. It touches upon many themes, including the controversial topic of how society treats prisoners with mental illness. We interviewed the author via e-mail on writing, how social issues can be addressed via literature, and the attraction of goodness versus the boredom of evil.

What is your background as a writer?

Casper: I was for many years a classroom teacher. When it comes to a writer’s background, there is both a good and a bad side to this. Many skills and techniques in play in teaching become impediments to writing for an audience. Good teachers repeat, elaborate, and review when students do not get it. There are subtle ways a writer can also do that, but writers seldom get a second chance. Students are a captive audience. Readers can flee with the first page that does not go as it should. That is where a good editor is essential.

I have to laugh when I read that some declining celebrity or failed politician is at work on a novel. Novel-writing is fast replacing quitting ‘to spend more time with family’ as a pretext for bailing out. I am not sure why the whole activity has such a mystique around it. It does, though, take a genius to write a really good one. Some of the best novelists, for example James Hilton and Sigrid Undset, are now all but forgotten. Sensational crime is a surer path to immortality, not that I recommend it.

Is Everywhere in Chains your first novel?

Casper: Everywhere in Chains is my second published novel. The Far End of the Park, self-published by Farhaven Press in 2011, is an abridgment of a longer work also featuring Father Ulrich, and with the title Upon a Time in Paradise, not yet submitted anywhere and being rewritten.

You are from the United States but are now living in England. Do you see differences in how each country deals with prisoners with mental illnesses?

Casper: The criminal justice system in the United Kingdom is somewhat more sensible than that in the United States. Prison sentences are more reasonable and proportionate. Far fewer people per capita are incarcerated. Nevertheless prison conditions are bleak, and treatment of the imprisoned mentally ill every bit as deficient, focusing on drugs used to control inmate behavior and little else. Rehabilitation and redemption continue to be empty, self-congratulatory concepts.

In both countries there is a building consensus that prison is the wrong place for seriously mentally ill people, and that society needs to focus on treatment before things get to that extreme. The views of my character Esther Corrigan are beginning to take hold. It is about time.

Back to the novel—Everywhere in Chains really conjures up the atmosphere of the American Midwest, and the changing landscape of rural America. Was this influenced by your upbringing?

Casper: I do not write fiction with an autobiographical connection, except in the broad, often convoluted way that many writers find their material lying around somewhere in their lives. There has to be a touchstone or an old closet in it somewhere; otherwise it can become empty fabrication, possibly entertaining, but only haphazardly true to life.

I think it is vital to place a story in settings where the writer’s emotional attachment is evident, not only attachment to the place itself, but also to its people. Often this is best dealt with at a distance. Willa Cather went to New York to write about Nebraska. Hamlin Garland, another Midwesterner, settled for a time in Boston. Robert Louis Stevenson never settled down anywhere for very long. His tales unwound in his own life’s wanderlust.

I grew up in a Midwestern rural countryside not far from a village like Clay Corners in my novel. Much has changed since then, but despite these changes, many such villages remain as they once were, with all their streets ending in farm fields. Similar villages now find themselves in the vicinity of recently-constructed prisons. The proximity of a prison, often the area’s major employer, changes the adjacent social landscape forever.

Another instance: my mother’s family included French Canadian, Great Lakes fishermen and even here and there a lighthouse-keeper. I grew up overhearing the lore of Lake Superior shared after dinners, in twilight on front porches and wherever men of the family gathered. They spoke of the ships, the storms, the seasons, and the islands with their sometimes fog-shrouded mysteries. This led me to Bell Harbor, an imagined place but nonetheless one that is grounded in a reality they knew, and I experienced secondhand.

The girl at the center of the plot who is searching for a father she never knew—her name is Penelope. Is there a little Homeric influence there?

Casper: The Homeric allusion, the paradigm of an odyssey with renewed faith and reconciliation at the end of it, is a useful way to approach Everywhere in Chains. Life for most of us is a series of such journeys. At one time or another, we have all sailed between Scylla and Charybdis.

Thinking of Homer’s Penelope, I am also reminded of a most memorable line from Milton: “They also serve who only stand and wait.” This certainly applies to the lives of Penelope Lister and her aunt Charlotte who says, “When someone you love is in prison, your heart goes there with them and stays for as long as they are there.”

I admire Father Ulrich’s tender response to this, but for that, the reader will have to read.

I also think it revealing that Penelope Lister does not want to be called Penny, more grist for the reader.

It’s often been noted that it’s easier to create believable (or at least compelling) villains in fiction, while it is harder to create a compelling depiction of goodness. Good characters are often accused of being unrealistic, especially now when anti-heroes populate so many of our books and movies. Any thoughts on this?

Casper: Yes, most of us associate realism with human frailty, flaws, and villainy. The more of that in the picture, the more we are inclined to suspend disbelief. One hardly ever hears that a fictional villain was too bad to be believable, or that a sinner too sinful.

I am really fond of the characters in Everywhere in Chains, so much so that I hated to see the novel end. I enjoy writing about people who are easy to like. I hope this comes through: my interest in them, my admiration, and my respect for them.

Writers of the rural scene sometimes diminish and ridicule its inhabitants in various ways meant to encourage a feeling of sophistication and superiority. I abhor this approach and think of it as a kind of fake realism. I myself admittedly have a bit too much fun at the expense of my hotelkeeper Fred of Ed’s, with his suspicions and wild-eyed conjectures. Nevertheless, I always look forward to his next appearance in the midst of matters otherwise serious.

In writing Everywhere in Chains I was striving for high contrast between the characters and the flawed institutions in which their lives are entangled. I kept evil on the periphery, though never out of sight, while focusing on the interplay of likable characters, and a plot seasoned with humor. Mark Twain and Charles Dickens are absolute masters of this technique. Both are sometimes accused of not being true to life.

If I had chosen to create a thoroughly lurid portrait of Father Lyle, no one would have questioned it, and few would have wondered if the depiction was true to life. Instead I did the unthinkable, and killed him off in the first chapter. From the perspective of book sales, this was probably foolish, but Father Lyle did not interest me. In fact, he was the one who was boring.

Can you say more about the idea that evil is boring and goodness interesting? And how does it relate to the realism of your novel?

Casper: When Father Ulrich is attempting to explain the tedium of hearing confessions, he says to Marvin, “Sin is boring and predictable; virtue requires some imagination.” I hope this is evident in characters like Felix, Ralph and Esther Corrigan, Marvin, etc., ordinary people trying to do the right thing in a world that often gets things wrong, “a broken world,” as Father Ulrich describes it at the end. I think this is the way life is, at least sometimes, not always. But always does not make for an interesting story.

All his priestly life Father Ulrich has been wading knee-deep in human failings, and has spent enough time in those troubled waters to know how predictable and boring are its characters and situations, not those we invent to attract a crowd, but the real things. Just try to tell people that the folk of Sodom and Gomorrah were bored out of their wits. No one would believe it, for the fact is that Fifty Shades of Goodness will never be a best-seller, and no one will make a film of it.

To give this a Chestertonian twist, we never tire of hearing about the tiresome. I sometimes think the best, most fitting punishment for people in Hell would be to force them to keep on doing what got them there in the first place.

Of course villainy is to be found at the heart of Everywhere in Chains, and short of that, a lot of small-minded, human nastiness. For the most part, though, I attempt to keep this in the background, while paying much more attention to its aftermath.

There is also immense social and institutional failure symbolized by Shade Creek Penitentiary and its sinister black bus; the two bullet holes in a rural mail box outside Penelope’s home; the broken weather vane, symbol of a directionless world; the near riot in Bell Harbor at the end; the tragic fate of Warren Hall, shared by those who become victims of his punishment; and chains, not just those that bind and imprison us, but those that connect us in the sort of world envisioned by Rousseau in his Social Contract.

I do not write about wizards; zombies, soothsayers, time-travelers, and the like. We live in an age when people believe in evil and doubt virtue; accept the fantastic as ordinary and reject the ordinary as fantastic. Chesterton must have said this somewhere.

In order for a novel to be successful as art, a writer has to avoid propaganda. But nevertheless, social, moral, or religious issues can be explored without resorting to didacticism. What do you hope people will take away from the story you’ve written?

Casper: Hardly a novelist of note has not dealt with these issues.

A storyteller’s aim is both to entertain and to teach, or at least to get a discussion going. To be sure, this requires a sometimes delicate balance. Mark Twain left us possibly the best example with Huckleberry Finn.

In the Twain tradition, I hope my reader enjoys the story, finds within it much to ponder, both laughs and cries along the way, and does not wonder why on earth I wrote it.

Leave a Reply