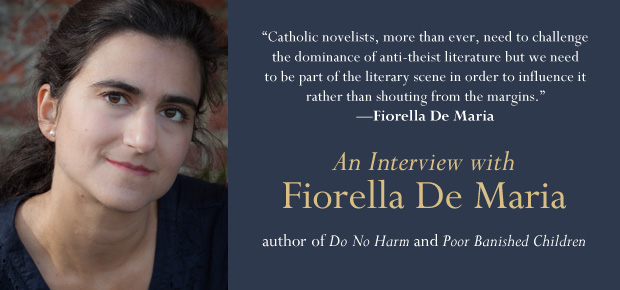

Fiorella De Maria is the author of four novels, including two published by Ignatius Press: Do No Harm and Poor Banished Children. Her other novels are The Cassandra Curse and Father William’s Daughter. Her poetry and short stories have appeared in such publications as Dappled Things. She and her family live in England. Ignatius Press Novels interviewed her via e-mail.

In a previous interview with Ignatius Insight, you described wanting to be a writer from a young age. Do you think being exposed to good art as a child played a role in that?

De Maria: Definitely, perhaps more than anything else. I learnt how to write through reading incessantly. I worked my way through all the classics—the Narnia stories, Alice in Wonderland, then later on Dickens, Austen, Eliot— but I also read a lot of modern, good quality fiction. When you read books as a child, it stretches you in all kinds of ways without you even realising it; your vocabulary improves, you learn the way adult authors articulate ideas, your imagination blossoms. I was also fortunate enough to live near a theatre and was taken to see plays from an early age where I could experience a very different, very immediate form of creativity. I remember being taken to see the original play version of Peter Pan and trembling with fear at the sight of Peter and Wendy stranded on a rock in the middle of a darkening stage, with Peter saying, ‘to die would be an awfully big adventure!’ It amazed me how real it all felt.

Now that you have children of your own, how do you go about introducing literature to them?

De Maria: My children are still very young (the youngest is only one and the eldest seven) but I encourage the older ones to read for pleasure and tell them some of my favourite stories on car journeys. I also try to read to them at mealtimes if there is time, though I have found it can be quite challenging. I was reading through a childhood favourite, Annabel’s Raven, recently and I was laughing so much I had to hand over the book to my husband. I think my children thought I was crazy!

What is your creative process like? Do you have a favorite bit of writing advice?

De Maria: I usually start with a single idea and the characters and plot develop around it. For example, with Do No Harm, it started years ago when I was speaking at a conference and a doctor asked me what doctors in Britain were to do if they were presented with a living will instructing them to remove a patient’s food and fluids (so that the patient would dehydrate to death). As I answered, I think I used the words ‘under pain of an assault charge’ and I just thought, ‘But what if a doctor was charged? What would happen to him?’ The whole novel sprang from that ‘what if?’ moment.

I usually write the opening chapter and the climactic chapter of a novel first, but avoid detailed plans as I prefer the adventure of seeing where the narrative takes me and it ALWAYS goes in a direction I did not initially intend. The characters will develop in a way I did not expect or some small plot detail added at the last minute will change the momentum of the story. I would like to pretend I sit in a book-lined study, writing in a state of reverie for hours with Gregorian chant playing softly in the background, but with four young children I tend to write in snatches and have trained myself to focus very quickly.

The best bit of writing advice I have ever been given is a variant on some words of wisdom given to my sister-in-law when she started at drama school. She was told: “If you can think of anything else you might rather do than be an actor, go and do it. You don’t train as an actor if there is ANYTHING else you would consider doing with your life.’ I think the same is true of writing. I get teenagers coming to me with their work, convinced that they are one step away from stardom and a multi-million pound royalties’ cheque, but the overwhelming majority of authors are not wealthy, the majority are not celebrities, but all of them write because they love to write and can’t imagine doing anything else.

Ignatius Press has published two of your novels, and they are very different: Poor Banished Children is a historical novel, and Do No Harm is a modern legal thriller. Are you more comfortable writing fiction set in modern times, or do you prefer the historical?

De Maria: I don’t really have a preference in terms of setting. Poor Banished Children was always a novel I wanted very badly to write. However, I knew it was going to be such a challenge artistically, emotionally and on so many other levels that I did not even consider embarking upon the project until I had two other published novels under my belt. I think writing a historical novel poses many more challenges for a writer, but I found when it came to writing a contemporary novel that there were all kinds of traps I had not anticipated. With historical fiction, it goes without saying that a large amount of research will be required but all novels require research unless the author insists upon only writing about what she knows, but this is not always immediately apparent. For example, most of us have had some contact with hospitals, either being admitted to hospital or visiting loved ones in hospital, but when I came to create a hospital as a work environment, I quickly became lost. I ended up spending hours questioning an infinitely patient doctor about the minutiae of life in Accident and Emergency—would he wear a white coat? How would he address a junior doctor or a nurse? What’s the name of that plastic thing they insert into the back of your hand? Do doctors use expressions like ‘heart attack’ or ‘nervous breakdown’? Then I had to go through the same process with a barrister, as well as spending hours poring over the transcripts of medical trials. There is a huge amount of protocol and tradition associated with the English courts and I couldn’t afford to make mistakes or I knew someone would pounce upon the fact that the defence counsel had bowed at the wrong moment or used the wrong term. That is the real risk with modern settings, imagining that you know more than you really do. It was a massive learning curve.

Poor Banished Children is set in 17th century Malta and moves to Africa as well as England. What kind of research went into preparing the novel?

De Maria: I think I spent around two years in total researching the subject. One of the most common pitfalls in historical fiction is the ‘modern mindset’ reflex that I think many authors struggle to suppress. By that I mean the temptation to create thoroughly modern characters expressing contemporary ideas, attitudes and behaviour, prettily dressed up in period costume. I wanted the characters to be completely period appropriate. I started out reading as much about the period as I could; academic studies but also eyewitness accounts where possible. I was living in Cambridge at the time and was fortunate to be able to meet with experts in a number of fields—the slave trade itself, piracy, life at sea. Cambridge has experts in pretty much everything and I was very touched by how generous people were with their expertise. I spent hours chatting about the tiny details of the Salé market over afternoon tea. A ballistics expert worked out how my heroine could cause an explosion without being blown up herself—he suggested finding a way to get her behind the foremast so that she would be caught in the blast shadow. A priest helped me out with the confessional sequences. I remember another academic bringing out exercise books crammed with notes in multiple languages, information gleaned over years of study. On one hilarious occasion, I invited my friend John over for dinner with his girlfriend so that we could discuss various plot difficulties. At one point over coffee and mints, we ended up acting out the moves of a combat scene in slow motion whilst my husband and John’s girlfriend sipped coffee nonchalantly and discussed her accountancy course.

I think it was Chesterton who noted that two of the hardest things for most people to express are gratitude and the desire for forgiveness. Warda, the protagonist of Poor Banished Children, has hardships that further increase this difficulty. How do you go about entering into the mind of someone who has endured so much?

De Maria: In some ways it is very hard to step into the shoes of a character such as Warda because of the extraordinary suffering she goes through, but in other ways I found the imaginative leap came quite naturally. A reviewer said that I demonstrated an understanding of the psychology of slavery, but more accurate would be to say I have an unfortunate understanding of the psychology of abuse and there is considerable overlap. My mother went through very horrific abuse as a child which has haunted her all her life. My debut novel The Cassandra Curse was partly based on her stories. She also had many friends who had had similar upbringings—I think it is in human nature to seek out kindred spirits, particularly where there is a history of suffering—and it meant that I grew up surrounded by people whose lives had been overshadowed by cruelty and who were struggling to make sense of what had happened to them. I witnessed both the extraordinary fortitude of adults who had been through unimaginable horrors and found healing, but also the raw emotions of those still battling with grief, bitterness or hatred. I wanted Warda to be completely psychologically plausible and drew heavily on my childhood memories to create her strength and courage but also to confront the darker consequences of unresolved suffering. I know some people have criticised Warda’s behaviour at different points in the book and protest that she should have been a good girl and dealt with her situation better, but suffering brings out the best and the worst in people. I was not prepared to create a sentimental lie and pretend otherwise. The subtitle for Poor Banished Children might read: ‘There but for the grace of God go you or I’.

Your most recent novel, Do No Harm, deals with current trends both in law and culture in England. Prominent Britons, including the fantasy author Terry Pratchett, have been calling for the legalization of assisted suicide. It’s into this climate that you plunge your main characters. Have you dealt with this mindset yourself?

De Maria: Unfortunately, public opinion is increasingly in favour of assisted suicide and as you rightly say, a number of celebrities have given their name to this cause. I come across the ‘right to die’ mantra very frequently, a lot of it is fuelled by fear of suffering needlessly at the end of life, a desperation for control but also misinformation. Britain virtually invented the modern hospice movement, we have made huge advances in the provision of palliative care but many do not even have a clear understanding of what assisted suicide actually involves. A paediatric nurse once told me that she was in favour of child euthanasia because she had seen doctors forcing terminally ill children through pointless and distressing treatment simply to prolong their lives by a few weeks and she could not bear seeing them suffering like that. She had never heard of double effect and did not realise that what she was actually arguing for was not euthanasia at all.

One of the reasons I wrote Do No Harm was that I wanted to explore the subject from the perspective of a doctor because much of the debate tends to surround the individual patient and their desires/rights, but seldom considers what it would mean for a professional to be expected to kill someone or to stand back and watch a patient die needlessly. A Dutch physician described euthanasia as being when ‘your worst nightmare comes true.’ It is all very well to talk about the right to be killed (which is what we are talking about here, no one requires a right to die) but that means that someone who has been trained to heal has to become a killer. At one point in the novel, Dr Kemble asks: “Is this the sort of society you want?” In many ways, that is the question the novel poses to readers.

What do you think is the role of the Catholic novelist in our culture?

De Maria: I would like to see Catholic novelists bringing the richness of the Catholic faith into the public consciousness in the same way authors like Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh did in the mid-twentieth century. We have a proud Catholic literary tradition and we should be in the midst of a great literary flourishing but for all sorts of reasons that has not happened. We cannot simply blame aggressive secularism for stifling Catholic culture either, I am very keen to point out that there has not been an easy time to be a Catholic in Britain for the past five hundred years and we should not have suffered the crisis of confidence we are currently experiencing in Britain and beyond. If a culture turns in on itself it can only stagnate.

Catholic novelists, more than ever, need to challenge the dominance of anti-theist literature but we need to be part of the literary scene in order to influence it rather than shouting from the margins.

Obviously, Catholic messages will be better received by a Catholic audience than one that is ambivalent or hostile to Catholic thought. What do you think Catholic authors can do to reach outside that core audience?

De Maria: In the end, Catholic authors have to write fiction not propaganda. I think a lot of Catholic authors and commentators realise this. I read somewhere on the IP Novels website a warning about writing becoming ‘sterile’ and ‘safe’ if there is no self-examination and authors simply critique secularism or modernism. That really hits the nail on the head. Too many aspiring writers set out to use writing as a platform to promote Catholic teaching and the predictable result is preachy and formulaic. Novels are not textbooks but if they are engaging with compelling plots and convincing characters, the Truth will shine through. I think a good story can appeal to anyone, even if Catholic readers will glean the most from its message.

What are you currently working on?

De Maria: I am working on another novel at the moment. Without wishing to reveal too much, it is set just about far enough into the past to count as a historical novel and the setting moves between Malta and England.

Leave a Reply