On this seventh day of Christmas, with the stress of holiday visits fading and the new year hard ahead, I’d like to look at the recent metaphor, widely used, of a war on Christmas.

It’s an idea touted in one venue and mocked in another. The idea is that overdeveloped political correctness, a retreat of religious culture under the advance of cultural secularism, corporate money-grubbing cowardice, and the vagaries of government regulation have colluded to restrict the traditional, common observance of the season. That, in essence, you can’t say “Merry Christmas” to anyone and no one is supposed to say “Merry Christmas” to you, and if anybody does so it better not be on public land. Spend your money, stuff your stockings, and shush.

It’s not all the way wrong. The people who mock it most generally whack at straw men instead of the real issue, but they’re sometimes aided by a sloganizing of the worry that’s just as bad. When “Keep Christ in Christmas” turns into a variation of “Say Christmas or Else”—in practice or in words—I think it’s fair to say the wheels of this war wagon are about worn off. The former sentiment recollects and witnesses; the latter scolds and threatens.

What Christians must not be drawn into is waging their own war on Christmas. And yet. What do we call a push to make ourselves big on the commemoration of God’s smallness? Are we in danger of becoming Bizarro Scrooges, humbugging away in the opposite direction?

A Tale of Two Christmases

When people become defensive about Christmas, it’s on two levels. One is the generous, social, culturally central celebration of Christ’s birth, and the second is the birth itself: austere, isolated, secret, and mutely glorious. Scrooge and his conversion to man belongs to the former, while Christ himself and certain poor shepherds belong to the latter. There’s nothing evil or disconnected about a Dickensian Christmas, but it is naturally incomplete without the primary sense—that is, the Nativity.

The goods of the Dickensian Christmas are abundantly on display in A Christmas Carol, of course. Dickens presents an argument for the season that is prolonged, convincing, and humane. But it generally stays on the human level; the prayer of the Cratchits and others exudes the warmth of those praying and the moral lesson of the season without grappling overmuch with the season’s mystery itself.

The goods of the Nativity, on the other hand, are transcendent, and cannot really be had other than in their religious observance. The biblical account of Jesus’ birth and Christmas Mass (redundant as that is in English) are primary, with popular devotions like staging the Nativity, Las Posadas, and the singing of hymns all illuminating the space outside of that. These things take us out of time itself and back to the manger, to God’s personal revelation to the physical world.

The popular devotions are in the outer realm with the Dickensian Christmas, though closer to the Nativity. The Nativity is the still point, and everything else exists in reference to it. The whole strength of these secondary observances, in the Christian sense, is that they do point back to it—”Merry Christmas” reminds us, if briefly, of God among us. The peril in these secondary observances and concerns is that they overtake the primary sense, and we end up squabbling over words and decorations—even over the practices of giving and being family—instead of the essence.

How to Lose a War

Someone with his eyes fixed on the Nativity but greatly swept up in the goods of the Dickensian Christmas is G.K. Chesterton. He is particularly good in articulating what the benefits of a public Christmas are, and no less amid the general incomprehension of its participants. Even someone who doesn’t believe, he says, but “whose childhood has known a real Christmas” will always have available a mental link

between two ideas that most of mankind must regard as remote from each other; the idea of a baby and the idea of unknown strength that sustains the stars. His instincts and imagination can still connect them, when his reason can no longer see the need of the connection….

Here is something worth defending, something searingly hopeful and mysterious, and intimately tied to the Incarnation. The experience of a “real Christmas” is at the heart of much of the Christian reaction to the so-called war. But does demanding store clerks greet us in the correct words reflect this mystery? Does defending our cultural place by denouncing non-compliance and casting suspicion on our neighbors embody the daring of God’s infancy?

It seems to me that the only thing worse than the death of Christmas by means of cultural silence is that death coming by way of Christians training themselves to bristle, fight, nitpick, and sneer. Instead, Christians need to bear witness, and particularly where the world offers spite. That means internalizing the joy of the season and sharing it, not scrutinizing anyone else to see that they are. It may even mean ignoring provocation instead of giving a stout defense. It means getting small, imitating Jesus, and getting joyful, imitating the angels.

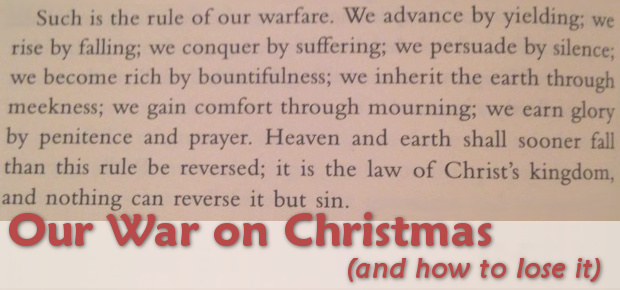

The words of Cardinal Newman convict me each time:

Such is the rule of our warfare. We advance by yielding; we rise by falling; we conquer by suffering; we persuade by silence; we become rich by [abundant giving]; we inherit the earth through meekness…. Heaven and earth shall sooner fall than this rule be reversed; it is the law of Christ’s kingdom, and nothing can reverse it but sin.

So that’s my plan. This is our secret weapon in the culture wars, what might save Christmas for everyone. If snide derision were met with Christian joy and humility, instead of a counterblow, I don’t think there’s a chance Christmas could ever be extinguished, because that is precisely the spirit of Christmas, before we ever get to gifts and family and decorations in the town square. Without it, I don’t see how Christmas in the full and public sense can even survive.

And it’s important that it does survive, Dickens and all. It’s a great beachhead in a hostile and uncomprehending world, and every Scrooge needs his chance. Chesterton again:

The great majority of people will go on observing forms that cannot be explained; they will keep Christmas Day with Christmas gifts and Christmas benedictions; they will continue to do it; and some day suddenly wake up and discover why.

Let’s hope so, for all of us. And remember that the Christmas season is still running. As such, and with all the joy in the world: Merry Christmas!

John Herreid

December 31, 2014 at 6:17 pm

Very good.

I suspect that the culture wars are more over than not, and that we lost. But there’s still often an attitude that people doing wrong are acting in full knowledge of Christian teaching, rather than being pretty much innocent of any knowledge of what the Church teaches other than a caricatured sketch offered up for lampooning by our media. So rather than shouting invective, the Newman game plan is probably the best strategy for the coming years.