“The riddles of God are more satisfying than the solutions of man.”

—G. K. Chesterton

The other day I was listening to an interview with an actor. He brought up the fact that he had been raised Catholic but fell away after reaching adulthood. His reasoning was something along the lines of “I realized the answers people gave me didn’t add up.” And so he left and became an atheist.

There are many other people I’ve spoken to who have a similar story. They were raised in homes where religion was practiced, but sooner or later they found the answers being given didn’t make logical sense to them or some crisis or other wasn’t placated by the pat responses.

What struck me about what all of these responses have in common is “answers”. But what about “questions”?

Earlier this week I happened upon an article by Martin Gayford on the artist Paul Gauguin, who was hardly a model of faithful behavior. In it, he explores why religion haunted the work of the painter. He attributes it partly to the religious education Gauguin had as a boy:

His imagination was filled with Catholic imagery and doctrine, and had been from an early age.

At 11 he had become a boarder at the petit séminaire de la Chapelle-Saint-Mesmin, near Orléans. There Gauguin underwent what he called ‘the theological studies of my youth’. He was taught by the Bishop of Orléans himself, Félix-Antoine-Philibert Dupanloup, an influential campaigner for religious education. The way that the Bishop’s instruction shaped the young artist’s mind is suggested by the questions Dupanloup posed in a text on the catechism. ‘Where does the human species come from? Where is it going? How does it go?’

The Bishop believed such rhetorical inquiries would linger in the pupils’ inner worlds, so that in later life, even if they were living irreligious lives and had lost their faith, ‘instinctively, instantaneously’ such questions would come into their consciousness. In the case of at least one ex-student he seems to have been correct.

This is a crucial point. Not that it isn’t important to provide answers for children via religious education—far from it—but that in addition to answers, the big questions should also be laid out there. Because in addition to the refrain of “the answers didn’t add up” that many people give for having left the practice of the faith, there is almost always a corresponding lack of interest in the big question of why we are here, who we are, and what we are for. As Fr. Robert Spitzer points out in his book The Soul’s Upward Yearning, a loss of interest and belief in the transcendent dimension of reality has lead to a great restlessness among many people. In his book A Turning Point for Europe?, Joseph Ratzinger (Benedict XVI) sees in the rise of drug use and terrorism a deep need for a belief in some form of paradise. According to Ratzinger, “Drugs are the pseudo-mysticism of a world that does not believe yet cannot get rid of the soul’s yearning for paradise… Terrorism’s point of departure is closely related to that of drugs; here, too, we find at the outset a protest against the world as it is and the desire for a better world.”

This has bearing on art. Many Christian artists seem to have difficulty asking questions, feeling that their work should be about providing answers. As said before, this isn’t entirely wrong, because answers are crucial. But questioning is also of great importance. Perhaps this is why sincerely questioning agnostics who still have a grasp on transcendence have often made better religious art than their religious counterparts.

So as we work to provide answers to the many people out there who are seeking, another thing we should be considering: are we asking the questions, and are we embedding those questions in the young people we are responsible for educating?

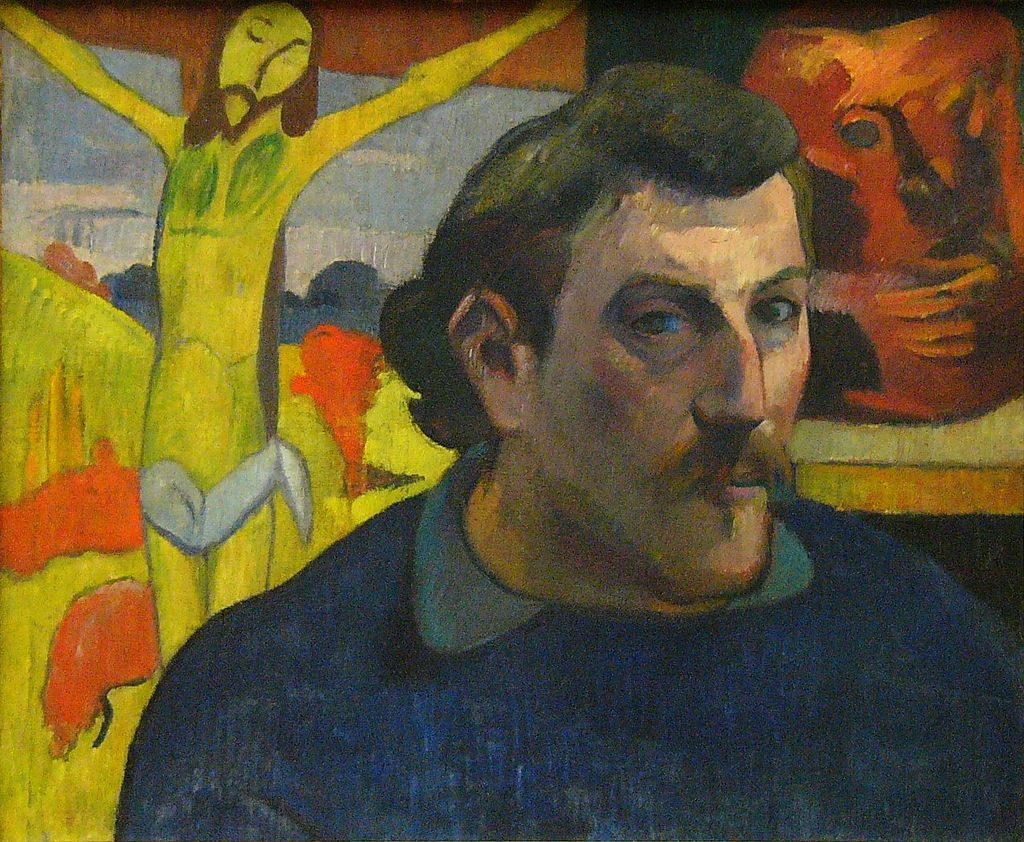

Image: Self-portrait with the Yellow Christ (Autoportrait au Christ jaune), 1890-1891, by Paul Gauguin, oil on canvas, 38 x 46 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

carleolson

January 1, 2016 at 6:15 pm

T.S. Eliot wrote (somewhere; I cannot find the exact quote) that much religious poetry is poor because it pious and insincere; it tries to convey what the poet thinks he should feel and think rather than what he does feel and think. Walker Percy expressed a similar criticism in different places; he insisted that novelists in a post-modern world should present the right questions, not provide pat answers. It’s hard to find a great Christian novel or film that is obviously didactic; they are usually much more indirect and allusive.

michaelnicholasrichard

January 3, 2016 at 7:49 am

I have often called J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings the most subversive work I have ever read. I mean that in the context of a relatively post Christian culture. When talking to non-believer fans of LOTR I see the effect it has on their “upward yearning” souls. They are touched by a grace that subverts their spiritual apathy, and they do not even realize it is happening.

Meanwhile, writers like Flannery O’Conner, Evelyn Waugh and Walker Percy offer works that are more openly “Catholic” but are subtle enough, and so well written as to appeal beyond its borders.

Graham Greene on the other hand, in my opinion, went even further an drove his upward yearning straight into the psyche of the bitter, post-Christian mind. So many of his characters are caught up in a subtle Smeagol-Gollum wrestling mach with themselves. He was so good at it, I think, because to his dying day he was entangled in that struggle — that conflict Terrence Malick referred to in his film, The Tree of Life, as the way of nature and the way of life.

In all the cases I cited above, I like to think of those works as assaulting the gates of Hell. Too often we read that assuring statement as if we are going to survive the assault of Hell upon us, when we should see it as a great sending forth, a call to march out of our refuge like an army issuing forth from a fortress.

When I wrote Tobit’s Dog, I was originally meaning it to be a much more subtle work than I produced. For me, there is always a point where the story begins to have a life of its own and Tobit’s Dog evidently decided it was going to be a more overt Catholic work than its author intended. Still, the messages I have received directly and indirectly indicate that there is a place, a need, for that as well. Encouragement for those who believe in the face of doubt.

That’s why I think of Catholic fiction as a big tent, with room for many types of work.

John Herreid

January 4, 2016 at 12:33 pm

Some great insights here. Michael, I think some of what you’re talking about here also comes up in Dr. Holly Ordway’s series on “good catastrophes”. First post here: http://ignatiusnovels.com/blog/2015/01/good-catastrophes-and-renewing-catholic-literature/

What worries me about a lot of my same-age peers and those younger than myself is what I mention in my post here: a near-complete lack of interest in the larger question of existence and purpose. What role has art has played in the rise of such an attitude? I dunno. But it is encouraging when new book, film, or song starts poking at that needling question, because it’s one that needs asking–now more than ever.

Carl E. Olson

January 4, 2016 at 2:38 pm

I should emphasize that I think a book or other work of art can be overtly Catholic without being needlessly didactic or lecturing in nature. Some Christian works come off as defensive or apologetic, whereas it seems to me that good literature and art should not be so. Many of my paintings from my early 20s were filled with Christian images, but often in cryptic ways–to the point that a fellow student at Bible college said he thought one of my paintings was “suicidal” in nature; the irony was that the work in question actually sought to depict the nature of man without God. So I guess he was right–but didn’t understand why such a depiction could be rendered by a Christian.

All that said, I think Michael is absolutely correct: Catholic fiction is a big tent, with room for many types of work. But perhaps not overly pious, sentimental works. Heh.

michaelnicholasrichard

January 4, 2016 at 2:53 pm

I should have written “way of nature and way of grace” in reference to Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life.

I think Carl is correct concerning the overly pious and (overly) sentimental works, though I find that people rarely agree with just what that is. I mean, there are people who love that Christmas shoes song.

Carl E. Olson

January 5, 2016 at 1:42 pm

Michael: There is certainly a gray area in making such judgments; I’ve had plenty of fun discussions about this very topic. I’ll readily confess that I sometimes enjoy movies, TV shows, or music that are sentimental or even overtly pious–but I never think they are great works of art, nor do I think they are really helpful in contemplating deeper questions or issues. Part of the issue, I think, is audience. I’ll enjoy a somewhat “tacky” Christian song, but would not consider sharing it with a non-Christian friend; he simply wouldn’t “get it” and, in fact, would likely (and even understandably) take it the wrong way.

But great art, in my mind, should be able to transcend such boundaries, due to a combination of craftsmanship, depth, and vision. Much “Christmas music” is sappy and sentimental–which can have a certain place, but does not make for great art, in my opinion. Handel’s “Messiah” is great art not only because of the craftsmanship and musical genius involved, but because of how it handles a great and grand subject, touching us on every level.

My didactic .02, for what it’s worth!